|

SQUARING FABRIC PIECES.

Blocking, squaring, straightening

- these terms are all synonymous to the technique of ensuring a fabric is properly

prepared for fabrication. That is, the warp and weft lines are perpendicular

to each other and a line cut following the weft thread is a straight line.

Symptoms of fabrics which

were not properly straightened:

Determining if a fabric

is off-square:

It is important, before

beginning a project, to know if or how much a fabric is off square. Cut the

leading edge of the fabric on the grainline using the most precise technique

for that fabric:

-- If a horizontal line

is woven into the pattern, cut along that line.

-- Or, pull a weft thread and cut along the pull line.

-- Or, if absolutely impossible to pull a thread, draw a line following the

printed pattern on the fabric.

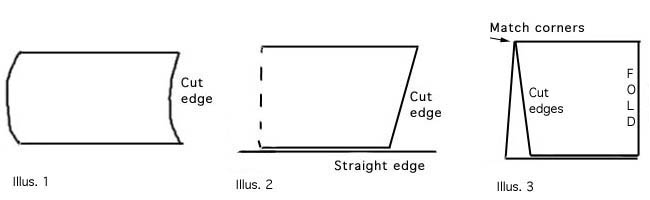

Sometimes, you can visually

see that a cut line is not straight. If the cut edge is curved (Illus 1), the

fabric was pulled thru harder on each side than in the center. Usually the cut

edge is slanted (Illus 2) because the fabric was pulled harder on one side than

the other. If the skewing is not readily noticeable, fold the fabric length

in half (Illus 3), aligning the corners and selvage edge on one side and let

hang. If the bottom corners do not come together, the fabric is not square.

Squaring techniques.

There are three methods by which you can square the fabric:

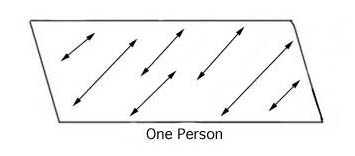

1. One person:

Grasp the fabric and pull at intervals across the length the fabric.

Fold the fabric in half lengthwise, matching the corners. If squared

to within acceptable limits, you are finished. Otherwise, repeat the

process.

|

|

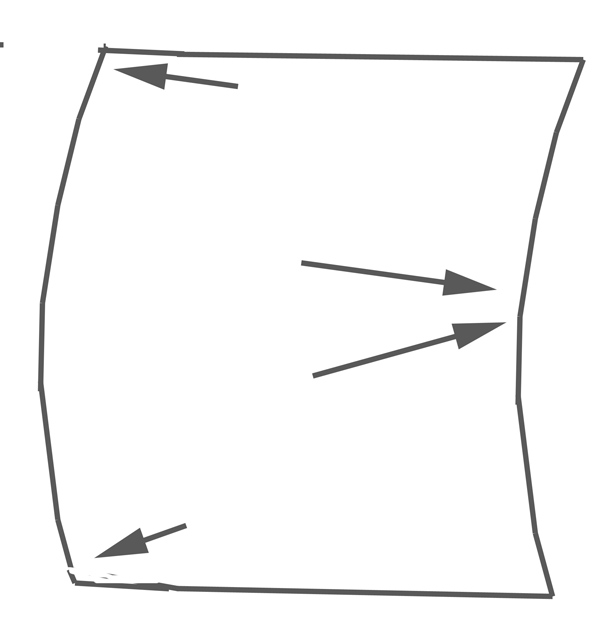

For concave fabrics, pull to block following these arrows.

|

|

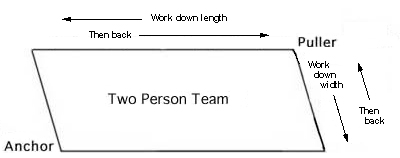

2. Two Person Team

For longer pieces

of fabric, it is best to have a second person. The second person will

act only as an anchor. They do not pull on the fabric, only provide

the stability.

|

|

There are several

reasons for using the second person as an anchor only: The puller

has complete control as to how much pull is exerted on the fabric;

Most fabrics don’t require the force of two people pulling; The

amount of pull will be more evenly distributed; Finally, the anchor

can be any kid or adult who happens to walk through the door - no

special training required.

With two people,

you will be pulling the fabric from the corners and along the edges,

thereby aligning all threads at one time. The anchor and puller each

grasp the fabric at diagonal corners (see the Two Person Team illustration).

The anchor braces and will not release the corner during this process.

The puller pulls firmly. You will see and feel the threads realign

themselves in the center of the fabric as you pull. Maintaining tension,

use a hand-over-hand motion to work your way down the length of the

fabric (the top of the illustration), grasping the fabric at 12-15"

intervals along the selvage edge. Return to the corner using the same

hand-over-hand motion and maintaining tension.

Continue to maintain

tension on the fabric. Using the same hand-over-hand motion, work

your way down the width of the fabric (the right side of the illustration)

grasping the cut edge of the fabric. Return to the corner using the

same technique and maintaining tension.

The reason for

working the tension on the fabric along the length and width of the

fabric is to straighten all the threads. Conventional teaching in

home-ec had us pulling only on the diagonal corners. This worked to

some degree, but only served to straighten the threads in the center

of the fabric. Pulling along the edges pulls the threads into alignment

throughout the cut piece.

Fold the fabric

in half lengthwise and check the corners. If squared to within acceptable

limits, you are finished. Otherwise, repeat the process.

|

3. Blocking on

the table:

This technique requires

a full-size workroom table. They are generally five feet wide by 8 or more

feet long. They are padded and framed with ruled sides. To block a stubborn

fabric using the table, lay it out flat on the table, aligning the selvage

edges with the side of the table. Clamp or pin one end of the fabric to

the table. You will have to pull the fabric so that the end of it is aligned

with the end of the table. It is very important to clamp or pin the fabric

closely to offset the tension you will be putting on it. If the fabric is

a loose weave which might tear away or fray, turn the first 2" under

and pin through both layers for increased stability.

At this point, if the

fabric will tolerate liquid, you can spritz it down liberally with distilled

water. The water relaxes the threads so it can be pulled. Take the other

side of the fabric and pull firmly, aligning it to the other end of the

table. Pin or clamp down securely. Steam the entire piece. Allow to dry,

then unpin from the table.

This is probably the

most effective treatment for straightening your fabric, but it does have

a couple of downsides: You must have a professional workroom table. The

fabric must tolerate steam and liquid. There is a possibility of uneven

shrinkage due to the steam and water which is applied. Until the fabric

dries, it will tie up your table for other projects.

Stubborn fabrics:

Many fabrics today are

treated with finishes and heat which lock the threads in position and resist

squaring. In some cases, you will have to exert quite a bit of tension on

the fabric to pull it into alignment.

Cut away the selvage edge.

Sometimes this edge will prevent the fabric from squaring up properly.

Some fabrics, if they

can be treated with water, will respond very well to the squaring technique

if thoroughly spritzed with distilled water. The water relaxes the threads,

allowing them to be realigned.

Fabrics which have been

treated with a rubberized backing (insulated and blackout linings, upholstery

fabrics, etc) cannot be straightened. The backing prevents this. The upside

here, though, is that they will hang square to their own selvage edges, regardless

of the warp and weft lines. This is because the backing stabilizes the fabric.

Do not try to cut on the straight of grain or block these fabrics. Simply

square to your cutting table or us the T- or L-square to draw your cutting

lines.

Finally, there are fabrics

which will not square at all or within acceptable limits. If you suspect a

fabric to be especially resistant to squaring, let it sit overnight to determine

if it readjusts itself out of alignment. If so, it must be rejected

Acceptable Limits:

Depending on the job,

there are various levels of acceptable limits:

Roman shades, soft cornices,

any valance with flat, squared sections must use fabric which is squared

to within one half of an inch. It is imperative they hang flat. Lining must

square to same limits.

Long panels, swagged

treatments, folded (jabots) treatments can work with fabrics which are squared

to within two inches. The closer they are to square, the better they will

work, but you do have some play here.

Unlined, unconstructed

treatments, puddled panels, scarf swags, etc. can usually be fabricated

without worrying about squaring.

Conclusion:

Squaring fabric is becoming

a lost art. Many new sewers are unaware of the importance of working with squared

pieces. When combined with a practice of cutting as close to the straight of

grain as the fabric and pattern will allow, you will ensure much easier fabrication,

installation and dressing of your treatments.

If you enjoyed this article, you might enjoy:

Fearless Pattern Repeats - Part 1 - Basics of pattern matching and handling various types of repeats.

Fearless Pattern Repeats - Part 2 - all about stripes & plaids

Half-Drop & Drop Match Repeats

Cutting Techniques

Squaring Fabric

Return to the Sew Easy Windows articles Table of Contents page.

|

![]()